This is a primer on marketplace design, market microstructures, and market-making from our combined 30+ years of experience in electronic trading at Tower, Citadel, Goldman Sachs and SGX. Whether you are a trader, a project launching a token, or an academic, we hope you find this four part series useful.

Part I: Marketplace Design: General theories and background information

Part II: Crypto Marketplaces: A discussion of some of the unique features of crypto marketplaces and how they are distinctive from traditional financial exchanges

Part III: Market-Making on Crypto Marketplaces: What does market-making actually mean, and how does it work?

Part IV: How to Work with a Market-Maker: Choosing and working with the right partner

Table of Contents

Overcome the cold start problem

Even with brilliant marketing and the most useful of utilities, most tokens and exchanges face a cold start problem. In the beginning, with few buyers and sellers, there will generally be low depth, wide bid-ask spreads, and price discontinuities, all of which increase the volatility of the asset and make it difficult and expensive for traders to engage. This is why many new exchanges and newly listed token projects will engage a designated market-maker.

The goal of any market-making activity should be to bootstrap liquidity for an exchange or token to the point where there is sufficient interest from traders to create organic liquidity. Eventually, if a market is very successful, a designated market-maker may no longer be needed at all.

Avoid fragmented liquidity

One common misperception among token projects is that it’s good to be listed on as many exchanges as possible. Actually, being listed on many venues fragments liquidity, which is especially challenging when liquidity is already low. We generally recommend to projects to list on 1-2 exchanges at a time and to build up sufficient organic liquidity before listing on new exchanges.

Similarly, for new exchanges, having too many products makes it difficult to build up sufficient liquidity on any one of them. This is why creating liquidity for options is a much more difficult problem than it is for spot markets – while there’s only one BTC, there are many BTC options with different strike prices and expiry dates.

Selecting Exchanges

Before the token generation event (TGE), there is the very core decision of where to list on, from CEXs to DEXs. Listing on DEX usually comes first, but there is significantly lower liquidity on DEXs.

The top-tier exchanges may not charge listing fees because they know the best tokens will earn them millions in fees, but the mid-tier exchanges may charge listing fees upwards of hundreds of thousands of dollars. However, here is much more liquidity on those exchanges, as well as other better access to retail markets. Top tier exchanges do require token projects do have a market-maker before listing. This helps with minimum liquidity and volumes. Price discovery is much more efficient on CEXs, so this actually reduces costs across the board. Therefore, most projects will begin to engage a token market-maker six-months to a month before their CEX listing.

What do exchanges look for when listing?

Overall – they are looking for tokens that will generate a lot of trading interest and therefore earn the exchange trading fees.

- Traction – community, activity, press and announcements

- Trading volume on DEXs if applicable

- Fundraising history – who your investors are, how much you’ve raised

- Legal KYC/AML

- If you are looking at multiple exchanges, exchanges will sometimes try to negotiate an exclusive listing.

Designated Market-Making for Token Projects

There are number of possible arrangements for token projects who wish to engage a market-maker:

- Retainers: the token project loans the market-maker both the token for trading inventory as well as quote currency (e.g. USDC/USDT), and pays the market-maker a monthly fee. At the end of the contract, the market-maker returns the full loan.

- Options: the token project loans the market-maker tokens for trading inventory, and gives the market-maker a call option on the loan. The market-maker can either choose to return the tokens or USDC/USDT, based on a strike price.

Designated Market-Making for Exchanges

Similarly, there are a number of different models for how exchanges can choose to incentivise market-makers.

- Retainers: an exchange can pay a market-maker a flat monthly fee to quote for the products on its market. This is most often used by new, start-up exchanges that do not yet have much organic trading volume.

- Fee tiers or rebates: most exchanges and marketplaces offer a tiered fee system, where makers pay lower fees than takers. Sometimes, makers fees can be zero or even negative (e.g. a rebate).

- Credits: which can be used to pay trading fees to market-makers who meet certain liquidity thresholds or post orders at specific times or in specific pairs, encouraging them to participate in particular markets and enhancing overall liquidity.

- Token / equity rewards: some exchanges create a rewards program to grant tokens or equity options to its market-makers.

Measure performance

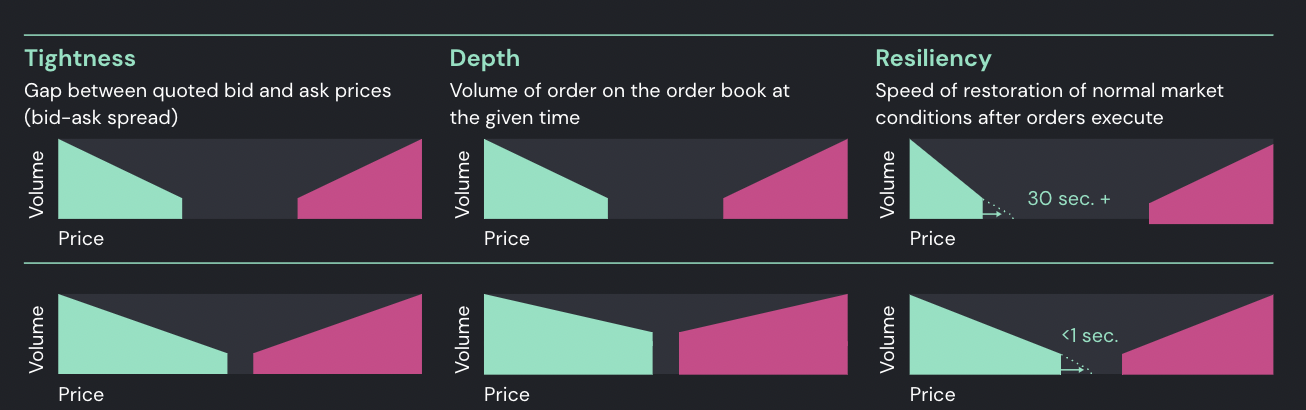

- Tightness, or spreads, are the core metric to hold the market-maker accountable for. With top-tier cryptocurrencies and stable coins, there should be the tightest spread of %0.05 -%0.1, while the rest of the pairs will begin to range from 0.1% to 0.3%. As the depth increases (increasing order sizes), the spread will as well.

- Latency (aka speed) is dependent on the quality of infrastructure of the market-maker and their integration with the exchanges.

- Guaranteed uptime: While it would be ideal for the market-maker to be able quote all the time, market volatility and technical issues can impact the amount of uptime.

- Slippage Maintenance: The token project will have to provide a loan to the market-maker to actively trade with, and as much of this capital should be used to maintain the KPI’s. However, there will a portion that is reserved for ancillary, but necessary activity like re-balancing and renewing of orders.

- Monitoring and Responsiveness: As crypto markets are volatile and 24/7, it is crucial that the market-maker is able to adjust based on the market conditions. As most market-makers trade a number of tokens, as well as market make on exchanges, they should also have visibility into different market movements.

- Reporting: The market-maker will likely have their own dashboards (usually based on Grafana), which they will share token results from, but there are also third party liquidity management dashboards such as Glass Markets.

During times of market volatility, the KPI’s are harder to maintain, but market-makers should still be responsive, be able to explain selling/buying pressures, as well as continue to quote.

Avoid Market Manipulation

While market-makers can help maintain volume, it is impossible for them to guarantee volume. Beware of any market-maker who guarantees certain volumes. Market-makers are also not in the business of manipulating prices. There are also a number of highly illegal and unethical practices, like order spoofing and wash trading.

In general, token market-making is common and necessary, yet a generally misunderstood service. The quality of project is core to its success, but having a competent market-maker can impact liquidity and therefore market perception from the very start.

Glossary

- Ask: The ask refers to the price at which you can buy an asset or security from a seller. It can be variously referred to as ask, the ask, or asking price.

- Bid: The amount a party is willing to pay in order to buy a financial instrument.

- Block Trade: A block trade is a large, privately negotiated securities transaction. Block trades are arranged away from public markets to lessen the effect on the security’s price. They are usually carried out by hedge funds and institutional investors via investment banks and other intermediaries, though high-net-worth accredited investors may also be eligible to participate.

- Central Limit Order Book (CLOB): An exchange-style execution method common in the equity world that matches all bids and offers according to price and time priority. It allows all users to trade with each other, instead of being intermediated by a dealer. Users can also see bid orders and sizes in real time.

- Clearing: The procedure by which financial trades settle; that is, the correct and timely transfer of funds to the seller and securities to the buyer.

- Depth: A market’s ability to absorb relatively large market orders without significantly impacting the price of the security. Market depth considers the overall level and breadth of open orders, bids, and offers, and usually refers to trading within an individual security.

- Exchange simulator: A programme that mimics a real-life stock market, allowing users and would-be investors to learn trading without assuming any real financial risk.

- Fully diluted value (FDV): The market cap of a project once all its tokens have been released into circulation. It is basically an estimation of a project’s future market capitalization.

- Latency: The time that elapses from the moment a signal is sent to its receipt. Since lower latency equals faster speed, high-frequency traders spend heavily to obtain the fastest computer hardware, software, and data lines so as execute orders as speedily as possible and gain a competitive edge in trading.

- Liquidity: Refers to how easily or quickly a security can be bought or sold in a secondary market. Liquid investments can be sold readily and without paying a hefty fee to get money when it is needed.

- Maker: Market-makers provide the market with liquidity and depth while profiting from the difference in the bid-ask spread.

- Private Market-Maker:An individual participant or member firm of an exchange that buys and sells securities for its own account.

- Designated Market-Maker: One that has been selected by the exchange as the primary market-maker for a given security. A DMM is responsible for maintaining quotes and facilitating buy and sell transactions. Market-makers are sometimes making markets for several hundred of listed stocks at a time.

- Automated Market-Maker: A type of decentralized exchange (DEX) that use algorithmic “money robots” to make it easy for individual traders to buy and sell crypto assets. Instead of trading directly with other people as with a traditional order book, users trade directly through the AMM.

- Market Cap: One measurement of a company’s size. It’s the total value of a company’s outstanding shares of stock, which include publicly traded shares plus restricted shares held by company officers and insiders.

- Matching: The procedure of finding pairs or groups of orders that are executed against each other. In its simplest form, there is one buy order and one sell order that are both executed at the same execution price and with the same quantity.

- Midpoint: The sum of the Pre-Announcement Price plus the Pre-Closing Price, divided by two.

- Over the Counter (OTC): The process of trading securities via a broker-dealer network as opposed to on a centralized exchange like the New York Stock Exchange.

- Price Discovery: The act of determining a common price for an asset. It occurs every time a seller and buyer interact in a regulated exchange.

- Quoting: A quote is the last price at which an asset traded; it is the most recent price that a buyer and seller agreed upon and at which some amount of the asset was transacted. The bid quote is the most current price and quantity at which a share can be bought.

- Request for Quote (RFQ): An electronic notification sent to all CME Globex participants that expresses interest in a specific strategy or instrument. The sender can request a specific size on the RFQ but is not obligated to show any preference as a buyer or seller.

- Resiliency: One of the measures of a market’s liquidity. It can describe how quickly prices in a particular market return to normal following a large order. It’s a similar concept to immediacy, which highlights how quickly an order can be fulfilled in a market.

- Settlement: Marks the official transfer of securities to the buyer’s account and cash to the seller’s account.

- Slippage: The difference between the expected price of a trade and the price at which the trade is executed. Slippage can occur at any time but is most prevalent during periods of higher volatility when market orders are used.

- Spread: The difference or gap that exists between two prices, rates, or yields.

- Spoofing: A form of market manipulation in which a trader places one or more highly-visible orders but has no intention of keeping them (the orders are not considered bona fide). While the trader’s spoof order is still active (or soon after it is canceled), a second order is placed of the opposite type.

- Taker: The term used for traders who are looking for trading options they can fill immediately, or as quickly as possible. Such an option could be a market order – remember a market order is based on immediacy.

- Trading Window: The window of time each day when we execute trades for clients.

- Uptime: A measure of an application or website availability to its end users. Companies measure downtime using a simple formula: (total availability time of the website * 100)/total time = uptime percentage.

- Wash Trading, also known as churning: An illegal practice where investors buy and sell the same financial instruments at the same time in order to manipulate the market.