What We Believe About Blockchain

Is blockchain truly a revolutionary financial technology, or is it all a massive bubble? This is the question that looms over institutional investors as they decide whether or not to get involved, and is more salient than ever after the collapses this year of Terra, 3AC, and now Alameda & FTX.

However, the revolution vs bubble framing may be a false dichotomy.

The “Railway Mania” of the 1840s was no doubt a bubble from an investor’s perspective. Investors poured money into railway companies at highly inflated valuations and eventually materialized big losses. Nonetheless, the “mania” led to 6,000 miles of actual railway being built across Britain, which had practical benefits for the country’s economy for decades after the bubble had burst.

Similarly during the infamous Dot-Com Bubble of the 1990’s, many companies with half-baked, unprofitable business models were created and then in short order collapsed. In retrospect, this “crash” was in fact the birth of a new tech-dominated age. Two decades later, the top five US companies by market cap are all technology firms (Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, Tesla), with a combined value that comfortably exceeds the GDP of Japan.

In other words, bubbles can develop around technologies that really are revolutionary.

What constitutes a “revolutionary” technology?

Technological progress is not linear. There are often time-bound explosions of innovation, whereby radically new ideas or paradigms change society permanently in a short space of time.

Cooking is an ancient example of technological innovation that enabled hominids to separate themselves from the rest of the animal kingdom. By freeing up the six or seven hours per day that great apes spend just chewing, early humans had time to evolve other game-changing innovations such as language, farming, and complex societal structures.

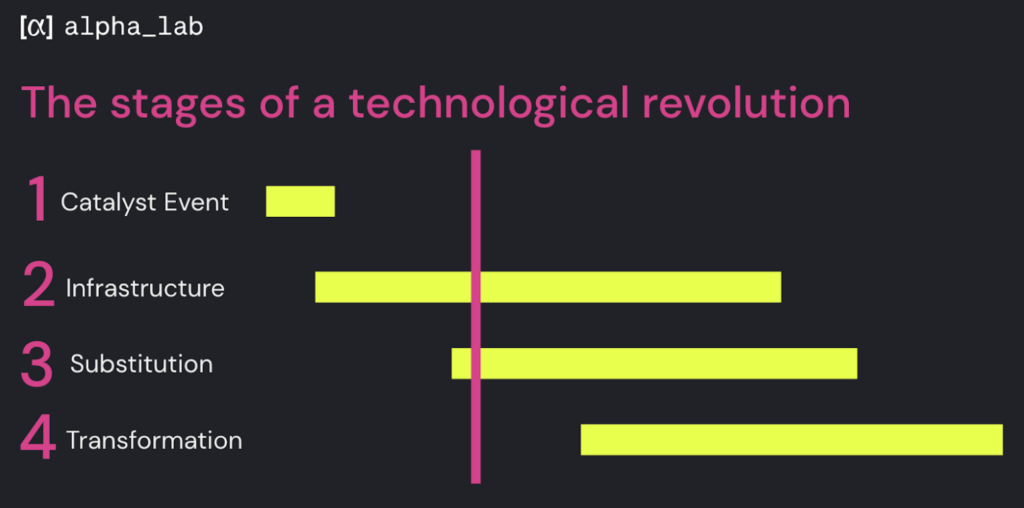

The following describes the typical trajectory of such a revolutionary paradigm:

- “Catalyst” Event: A new technology is developed that dramatically reduces the cost of a given, specific activity.

- Infrastructure: New infrastructure is created to take advantage of the reduction in cost.

- Substitution: With this infrastructure in place, new businesses emerge to replace the old ones.

- Transformation: The effects of substitution ripple throughout society to transform business models, supply chains, jobs, education, etc in a wide range of adjacent industries.

Let’s look at some concrete historical examples:

The Printing Press

- Catalyst Event: Gutenberg’s invention makes it possible to go from 40 pages per day (for a single scribe) to thousands of pages per day for a single printing press.

- Infrastructure: Within decades, hundreds of printing shops had been established all over Europe, and ships were transporting books overseas.

- Substitution: An out-of-work scribe could now opt to go into business as a printer or bookseller. The ability to produce vastly more books was a huge net positive for the economy as a whole.

- Transformation: The new availability of knowledge not only improved general literacy, but also had implications for scientific progress, trade, and the decentralization of political and religious power.

The printing press was more than just an innovation in publishing technology. It ushered in the end of the Middle Ages and allowed European civilization to level up (rebooting largely from pre-existing Greco-Roman models, encoded within now widely available literature). It literally changed the world forever.

The Internet

- Catalyst Event: In 1972, TCP/IP introduced the idea of breaking up information into very small packets, allowing any two nodes to communicate without the need for expensive dedicated lines.

- Infrastructure: Companies like Sun, Netscape, and AOL developed the hardware and software to exchange emails/instant messages and browse websites.

- Substitution: The proliferation of the internet precipitated the (still ongoing) decline of pre-internet industries (print advertising, fixed line telephony, physical records, and DVDs, etc.) forcing legacy firms to evolve or be replaced.

- Transformation: In addition to fundamentally altering the dynamics of commerce (e.g. by reducing the importance of physical scale), the internet is comparable to the invention of the printing press in its implications for the exchange of knowledge and redistribution of power.

The problem: identifying the potential

The effects of revolutionary technologies appear obvious in retrospect. When they first appear, they are often incomplete, flawed, difficult to use, and easy to underestimate or even ignore.

The president of Western Union William Orton famously described an early prototype of the telephone as “practically worthless” adding that the idea would “never amount to anything.” Even early proponents of the device saw it as a niche application, for short-distance use only.

What about blockchain?

Five years ago, an HBR article argued that the transformational potential of the blockchain lies in its ability to slash transaction costs, a promise that remains unrealized to this day. While it is possible today to move tokens across borders quickly and cheaply, the need to convert these funds to fiat via costly and time-consuming on and off-ramps largely neutralizes any blockchain-based benefits.

As long as fiat currencies are required to pay rent, buy food, or make payroll, blockchain cannot lower the cost of transactions in any meaningful way.

But what if lowering transaction costs is not, in fact, the true locum of innovation?

We believe that blockchain has the potential to revolutionize society in a more profound way, by dramatically reducing the cost of creating, transferring, and composing assets.

Sidebar: What is an asset?

For the purposes of this article, we are defining “asset” as anything that:

- Can be owned (i.e. not a public good, universal abstraction)

- Is durable (i.e. non-perishable)

- Promises future value

The “future value” of an asset can come from all or any of the following:

- An income stream (e.g. dividend payments)

- Utility (e.g. a car that can be driven)

- Trading value (e.g. a piece of art that can be sold).

The very earliest assets in human society included tools, real estate, gold, and other precious metals and stones.

The earliest records of loans – a financial asset – are found in ancient Mesopotamia 4,000 years ago, and the practice of institutional lending was common in Ancient Rome. Formal institutional borrowing began in the 1100s in Venice, home to an active market for trading government bonds.

The idea of publicly available, fractional ownership in companies (i.e. via common stock) originated in the 1600s with the Dutch East India Company. Later, many variations on stock and bond instruments, such as futures, perpetuals, and options followed, leading to the vast array of financial assets on offer today.

On-chain assets such as cryptocurrencies and NFTs – which are neither based on naturally occurring minerals (like gold) or created by governments (fiat currency), but by mathematics (e.g. via elliptical curves) – are arguably a fundamentally new class of financial asset, the first to be created in 400 years.

Step 1: Catalyst Event (Lowering the cost of creating assets)

Before cryptocurrencies, creating an asset was typically difficult and/or expensive. For example, one could:

- Mine gold, diamonds, or other precious metals / stones

- Form a government and issue bonds

- Launch a public company: generally requiring $100M+ of revenue, plus 5-10% fees to a small army of investment bankers, lawyers, accountants, auditors, and an exchange listing fee of $500k+

- Create intellectual property (e.g. music, art works, inventions)

- Develop real estate.

Just as social media made it possible to reach millions of readers without the need to buy ink by the barrel, cryptography allows anyone to mint an NFT for less than $50. While there are additional fees required to market or list such tokens, the cost is still trivial compared to that of an IPO.

This catalyst event has therefore led to a wild proliferation of new assets. At the peak of the most recent bull market (late 2021), approximately 1,000 new cryptocurrencies were being launched every month.

The first major proliferation of assets began in 2017, and became what is now referred to as the ICO Boom. Many were of low quality (if not outright scams), but the boom did establish cryptocurrencies on a new footing, by bringing them to the attention of mainstream investors.

As the scams and bad ideas imploded or were exposed, the average quality of the projects behind the assets improved and the sector as a whole gained credibility.

1. Value moves faster owing to the removal of friction. This is both good and bad. Speed and irrevocability can lead to a proliferation of fraud and hacks, which points to a need for infrastructure that does not reduce, but introduces more helpful kinds of friction.

2. Higher reflexivity and faster feedback loops. The barrierless nature of crypto provides an ideal environment for ponzinomics to flourish, but also for high quality projects to emerge more quickly. Promising high APYs will attract a large, swift influx of capital, driving up the price of the token until the supporting exponential inevitably gives way.

In the crypto markets, token price is established more by consensus than valuation. Many projects are so early stage when they launch a token, it’s impossible to form a valuation based on historical or comparable analysis. Hence, it is often a reflection of marketing and storytelling rather than careful reasoning.

Once an asset’s price is established (or even anticipated) at a certain level, it opens the door to creative incentive design:

- How do we bootstrap a marketplace or ecosystem by using tokens as rewards? E.g. Airdrops, X-to-Earn, Liquidity Farming.

- How do we coordinate work across a loosely affiliated group of people (different models of DAO’s).

- How do we govern projects?

Crypto enables a large number of economic and incentive design experiments, involving real people and real money, but the high noise-to-signal ratio means that it is harder to distinguish a product with legitimate utility from a ponzi scheme.

Step 2: Infrastructure Phase (Laying the foundations for mass adoption)

This is the phase in which most developers and commentators would classify Web3 as currently situated.

The infrastructure necessary to support a mainstream adoption of crypto has already developed considerably since the heady days of 2017. This includes:

- Alternative Blockchains: We are currently in a multi-chain world, with various alternatives to Ethereum vying for different segments. These include Binance Smart Chain, Avalanche, Solana, Aptos and Sui.

- Layer Two Solutions: Ethereum scaling solutions such as Optimism, Arbitrum, Polygon and Starkware have emerged as one way to address the ever-present blockchain trilemma.

- Research & Analytics: With the growing prominence of crypto, an ecosystem of ancillary services – research, analytics and consulting – arose to help investors evaluate assets, along with any number of influencers/shillers to promote them, and VCs to invest in them.

- Other types of infrastructure:

- RPC node providers (e.g. Alchemy, Infura, Blockdaemon)

- Wallets and custody (Metamask, Fireblocks)

- Developer Tooling /Analytics

There is an ongoing debate as to whether infrastructure or applications come first (TLDR: it’s a dance, not a sequence), but for the purposes of the four-part trajectory we are describing, we would categorize both as falling under the heading of ‘infrastructure’.

How far are we into this phase? With the value of cryptocurrency currently hovering around $1trn dollars, and Web3 increasingly a household word, Web3 is clearly out of the starting blocks. Comparing this to the global economy at $100 trn, it’s fair to say that mass adoption is still a ways off.

Ironically, the bear market may be a positive development insofar as it proves the legitimacy of the infrastructure firms that survive (such as Uniswap) and distinguishes them from those that don’t (Terra). This will attract not only investment but the innovative minds needed to solve the genuine scaling problems that would preclude mass adoption even if demand were there.

Step 3: Substitution (New businesses emerge to replace the old)

It’s not yet clear what form Substitution will take. Let’s not forget, many innovations have ended up achieving wide acceptance for use cases unanticipated by even the founders.

Bitcoin, for instance, began as a payment solution and has ended up as a worldwide social movement, with claims and objectives that are not found in the initial whitepaper. And as web3 is not a single solution but a sprawling mass of solutions, predictions are even harder.

One observable change has been the steady advance of traditional financial institutions into the world of crypto investing. Institutions are slow by nature. Notwithstanding, in 2021 alone crypto allocation by institutions rose to USD 9.3 billion (+36% YOY). The launch of crypto-backed products and blockchain-related services will likely continue hand-in-hand with the broader rise of crypto.

However, institutional acceptance is likely a lagging indicator. The real magic will take place in the form of genuine substitution – that is, the creation of new paradigms. While we are at the primordial stage, there is enough evidence to suggest the potential for the “blockchain-fication” of other industries:

Data storage: Cloud-based storage is expensive and insecure. This is a direct consequence of centralization. Decentralized storage using blockchain protocols (e.g. Storj, Filecoin) improves security and affordability, distributing the profits of data storage to a wider group of individuals. This again looks like a no-brainer, and given that data is the oil of the 21st century, a highly consequential shift.

Gaming: Gaming accounts for about half of blockchain usage, as there is broad usage for digital goods and the creation of economics for in-game assets. These assets can be traded or sold on secondary markets, giving players a way to monetize their game play. In addition to the Web2 games that have started applying blockchain technology in their games, there is also a proliferation of Web3 native games, many of which are play-to-earn, like Axie Infinity.

Advertising: The digital economy runs on ads. Getting rid of them altogether is possible but has disadvantages, in that it makes it harder for the less well-off to access services that are currently free at the point of delivery (Gmail, Google Docs). The BAT token and the accompanying browser Brave applies Web3 logic to this problem to allow advertisers to find their market more efficiently and consumers to retain control and monetize their attention.

Content: The “100/1000 True Fans” model states in theory that an artist can be independent and successful with the support of a modest following, without the hassle and expense of a record company. The emergence of NFTs and the possibility of royalty sharing provides the tools for such self-sustaining communities. Projects such as Album Trading Cards are at an early stage, but if the model can be made to work, it will be a classic triumph Web3’s ‘read + write + own’ paradigm.

Work: Traditional corporate structures are a reflection of the post-war generation’s idea of what work should be. Stable, 9-5, and with a clear hierarchy to climb. Employees rarely had decision-making input, and politics often crowded out initiative, leading to the Innovator’s Dilemma. Re-conceiving the corporation as an online collective, linked by a mission, gated by passion, and empowered by governance tokens, is already flipping the traditional paradigm on its head, not only in DeFi (MakerDAO) but also in the social impact space (GoodDollar).

Real estate: Fractional ownership opens up the possibility of liquefying real estate, making it possible to sell, buy and invest in properties on a far less restricted basis (such as RealT). The status quo is highly illiquid and stuffed with intermediaries, and would seem to be an ideal candidate for a web3 do-over.

Step 4: Transformation (Broader economy and society adapts)

Despite all of its problems, Web2 has reshaped the world and rewired our economies. When the Substitution phase has completed its first major wave, what fundamental changes will Web3 bring? In other words, what does a world in which one can create assets cheaply and quickly look like?

- Democratization: In reducing cost, technology breakthroughs re-distribute power. By granting access to those previously without the means or connections, suddenly information, communication, and (in web3) value exchange becomes possible for everyone.

- Liquification: When it is possible to ‘securitize’ any asset (including labour, property and possessions) it is possible to have a market where, in theory, money is no longer needed to facilitate transactions, and there is no advantage to being based in a given geography. This concept of the “DeFi Matrix”, popularized by Balaji, would be a watershed in global economic history.

- More (& stronger) communities: Given that it has its own currency and user base, a blockchain facilitates the emergence of smaller, self-contained and highly-aligned communities. This need not be a new group per se, but could be an existing town or region that wishes to operate in parallel with the existing financial system. This could accelerate the existing tendency towards localization and the importance of identity and values.

- Hyper-innovation: Innovation is a random process with a low-frequency/high-payoff distribution. As explained by Nassim Taleb in an often overlooked paper, the way to create the ideal circumstances for innovation is to run a large number of experiments (rather than investing heavily in a handful of projects). The proliferation of many highly-aligned communities – i.e. the opposite of a global monoculture – creates the ideal environment for innovation. We would expect the future to experience a reversal of the stagnation in innovation that many believe has characterized the last 50 years.

Conclusion

We believe that blockchain is a revolutionary technology, because nothing short of catastrophic failure in every single branch of the ever-expanding tree of possibilities will prevent a future that is not materially freer, more efficient and more prone to rapid improvement.

The challenge for any investor, at this point in the cycle, is the sheer ratio of signal to noise. Perversely, bear markets are ideal times to make long-term bets as the noise factor has (for now) been significantly reduced.